Eight Years of Squiggle Performance

/The Squiggle website is a place where forecasters can post their forecasts for the winning team and winning margin, and provide probability estimates for upcoming games of men’s AFL football, and see how well or otherwise they perform relative to other forecasters. The only criteria for posting there is that the forecasters must have a history of performing “reasonably” well, and must not include any human-related inputs such as bookmaker prices in their models.

It’s been running since 2017 and, since 2018, has included a derived forecater, named s10, which is a weighted average of the 10 best Squiggle models, based on mean absolute margin error, from the previous season. The MoS model had been included in s10 in every year from 2018 to 2024, but will be absent in 2025 due to a relatively lowly 22nd place finish.

In this blog, among other things, I want to get a sense of the extent to which that apparently below-average performance might be attributed to skill versus luck.

METHODOLOGY

To do this I’m going to simulate the 2024 season 10,000 times and calculate each forecaster’s MAE in every replicate, and where their MAE has them ranked for that replicate. The forecasts for each forecaster will be fixed across replicates, but what will change are the “actual” results of each game.

More specifically, the results for each game will be assumed to come from a Normal distrution with a standard deviation of 32 (or 29 in 2020, when the games were 20% shorter) and a mean equal to the aggregate bookmakers’ forecast (calculated as the negative of the closing line in the AFL Data file from AusSportsBetting) plus a value drawn from another Normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 8. We could assume that the bookies’ forecasts are exactly equal to the true expected margin for every game, but that seems unrealistic, as even the bookmakers surely must have some variability around absolute perfection. The value of 8 was chosen because it gives a spread of expected best and worst MAEs that is similar to what we saw in 2024.

(To be very clear up front, a potentially reasonable position to take is that the bookmakers did a relatively poor job this year, so anything using them as something of the benchmark for an “expected” season is flawed, and some of the excellent performances we saw might be the result of some forecasters having superior models to the bookmakers. It’s tough to come up with a way to test this, but I’m open to suggestions. Ultimately, what we need are the true expected margins for every game in the season.

In the absence of any such test it would be wrong to jump to firm conclusions about the relative contribution of skill and luck to the actual results we saw for 2024 and we should, instead, consider what’s here to be a first, interesting input to a deeper analysis.)

RESULTS

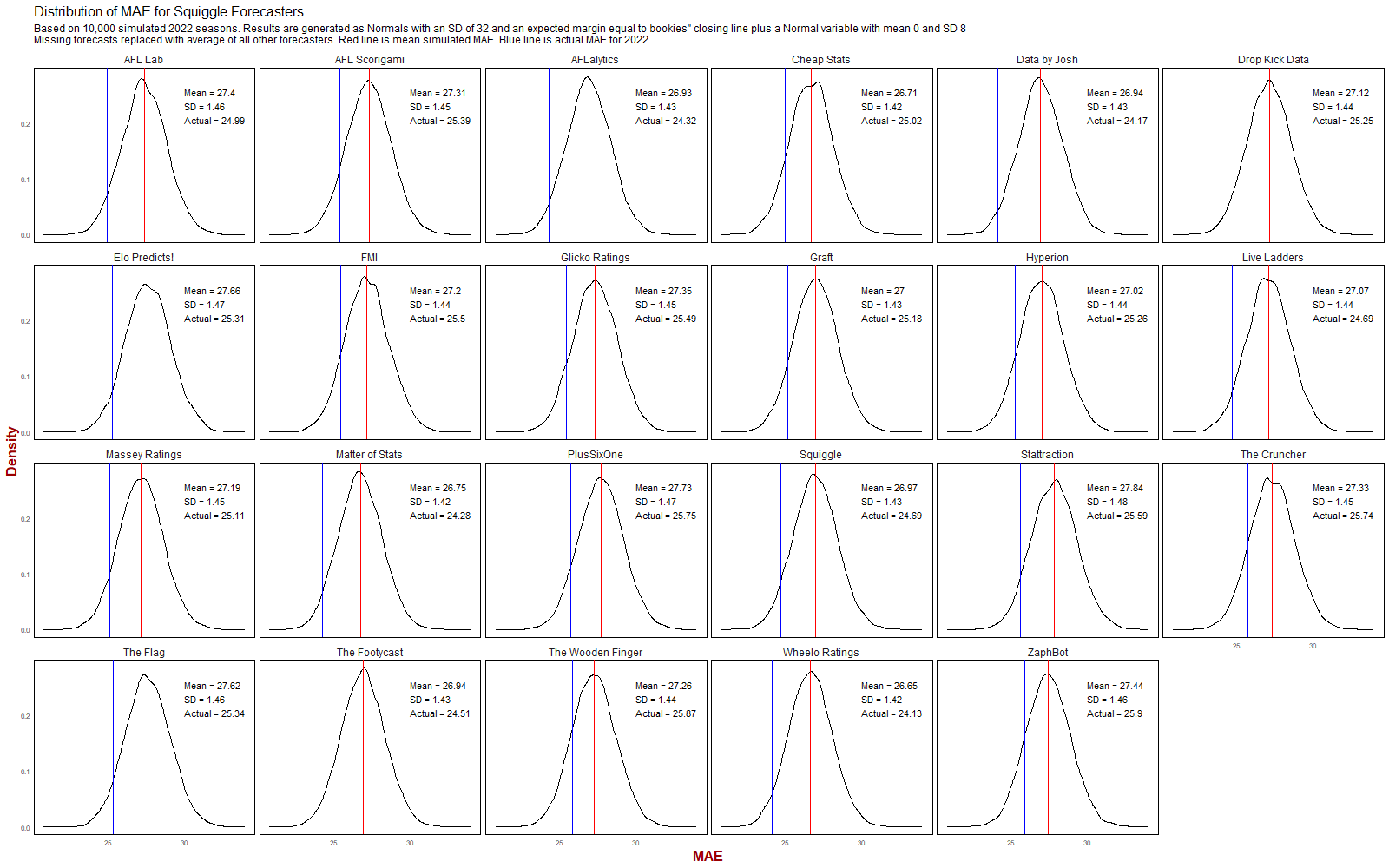

We’ll look firstly at the distribution of MAEs across the 10,000 replicates for each of the Forecasters, the details of which appear below.

The extent and direction of each forecaster’s “luck” can be measured by the gap between the red line, which is the MAE that the forecaster would have been expected to record in an “average” 2024, and the blue line, which is the MAE that the forecaster actually recorded.

If the blue line is to the right of the red line, the forecaster was “unlucky” and, conversely, if the blue line is to the left of the red line, the forecaster was “lucky”. The size of the gap between the red and blue lines indicates just how lucky or unlucky.

It turns out that I (Matter of Stats) was among the unlucky forecasters, my actual MAE of 27.34 points per game being 0.65 points per game higher than the expected value across 10,000 simulated seasons.

We can also look at how each forecaster ranked in the 10,000 simulated seasons and where in that distribution each forecaster actually ranked.

The first thing to notice from this chart is the broad range of rankings that virtually every forecaster enjoyed across the 10,000 simulated seasons. Consistent with this is the fact that, throughout 2024, the absolute gaps between forecasters with similar rankings were often tiny. Even at season’s end, the gap between 10th and 22nd was only about 91 points (or about 0.4 points per game).

In ranking terms, the big outliers are:

Finished ranked lower than expectation: Cheap Stats, footycharts, Glicko Ratings, Matter of Stats

Finished ranked higher than expectation: AFLLab, Elo Predicts!, Live Ladders, Massey Ratings, Zaphbot

Since the only way to be a big outlier is to rank quite highly or quite lowly, it’s no surprise that the forecasters on these lists tend to be from the extremes of the final rankings - in a sense, some forecasters had to be outliers - but from the viewpoint of assessing the extent to which a relatively poor ranking should be solely attributed to potential issues with the underlying model, what’s here, I’d argue, is interesting.

The final chart I’ll include for 2024 is the distribution of MAEs for all the forecasters that finished ranked in a given position in a simulation (ie we look at the distribution for all 1sts, all 2nds, and so on).

We see that the expected MAE for 1st is about 26.2, and that for 27th about 28.8. The actual values in 2024 were 26.4 and 28.6, which is what gave me confidence about using a standard deviation of 8 in generating expected margins from the Punters forecasts.

Since we have the script, why not run it for the other years of Squiggle?

SQUIGGLE IN 2023

A good year for all forecasters, with actual MAEs coming in under expectations, well under in the case of a few. Final rankings seemed reasonable in the context of expectations with the possible exceptions of AFLLab, Cheap Stats, and Graft.

SQUIGGLE IN 2022

An even better year for all forecasters, with actual MAEs coming in well under expectations. Final rankings again seemed reasonable in the context of expectations with the possible exceptions of Cheap Stats.

SQUIGGLE IN 2021

Most forecasters’ actual MAEs came in around expectations although a few were slightly worse. A few of the final rankings were quite distant from the expected values, in particular for AFLLab, FMI, and LiveLadders.

SQUIGGLE IN 2020

Another good year for most forecasters, with actual MAEs mostly coming in under expectations, although 2020 will forever carry the largest asterisk. Final rankings seemed reasonable in the context of expectations with the possible exception of The Flag.

SQUIGGLE IN 2019

Some variability in forecaster fortune in this season, with Fat Stats being most unlucky and AFLLab most lucky. Final rankings seemed reasonable in the context of expectations with the possible exceptions of AFLLab and Massey Ratings.

SQUIGGLE IN 2018

Most forecasters’ actual MAEs came in around expectations although a few were slightly better. A few of the final rankings were quite distant from the expected values, but with only 11 entrants, this is probably to be expected. The biggest differences were probably from MatterOfStats and Swinburne.

SQUIGGLE IN 2017

A poor year for all forecasters, with actual MAEs coming in well above expectations. Final rankings again seemed reasonable in the context of expectations with the possible exceptions of Figuring Footy.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

What to make of all this then?

For me, it’s made me feel a little less concerned about the 2024 performance of MoSHPlay - not that I won’t still be considering some further work on the MoS twins over the men’s off-season. It’s also made me aware of how variable the margin MAE results of a single season can be, provided that you buy into my methodology for simulating alternative versions of the same season.

One thing that did, initially, give me pause, was the absence of larger differences between actual and expected MAEs. If our distributions are correct, surely we should be seeing some 1.5 to 2 SD variations. After all, we’ve recorded them for well over 100 forecaster seasons.

That’s true, but they’ve not been 100 independent forecaster seasons, because inter-forecaster margin correlations are quite high in every season, so there will be a tendency - as we’ve seen - for all forecasters to be above or below their expectation. We really then probably have only 15 or 20 effectively independent drawings from the MAE distributions.

I’m not sure what this analysis means in any wider sense, but would be happy to hear from any of you in the comments below.